Dubbo is known as the gateway to NSW’s west and the home of the Western Plains Zoo. But few would pick the country city of 34,000 as a home to a world-class IT company which won the international award of best small business partner for Microsoft in 2006.

Dubbo? How? Largely on the back of one man, who saw the writing on the wall for the standard break-fix model in 2000 and wrote his own approach, which is used by more than 300 resellers around the world.

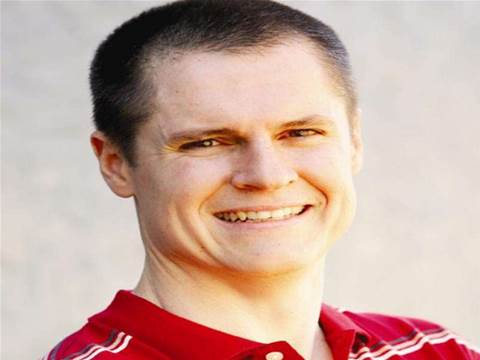

A career that starts and ends in Dubbo is always going to be less than orthodox. But in retrospect, it seems obvious that Mathew Dickerson was destined to be a success in IT.

When his school received its first computers, two Apple IIs in 1980, Mathew was writing programs on them three days later – despite being in Year 7. By the end of the year he had compiled a database for the entire student body which he then managed on behalf of the school.

“I remember doing the data entry, too. The teachers thought that was great,” said Dickerson. The school allowed him to keep a copy which he used to organise the 10-year reunion.

Back then, computer science was only studied by those wanting a career in programming Unix, and the subject itself wasn’t counted towards the Higher School Certificate.

Dickerson finished school and left Dubbo for Sydney, where he worked for life insurance company Prudential maintaining the fleet of “computers” for its agents in the field.

The agents carried briefcases containing a calculator-sized Casio and docket printer, from which they would produce graphs to show how much a superannuated person would be worth by retirement. Dickerson’s department wrote and updated the software, which the Casios ran on little tapes.

It was a step up from data entry, although a small one. “One of the exciting jobs I had there was to duplicate changes to the program onto a couple of hundred tapes. I had this really important job of inserting tapes into one device while it copied over onto another tape.”

After three years the expense and intensity of big-city life became too much and Dickerson returned home to the most depressed part of the economy since the Great Depression. In 1989 interest rates were at 18 percent, and there was incredibly high unemployment.

“There were some government jobs that didn’t seem that exciting, and so I just thought, stupidly and arrogantly, to start a business.”

Dickerson set up office in a bedroom at his parents’ place and started selling door-to-door from brochures. Two-way radios, the first mobile phones, computers, fax machines, car phones – any business-minded electronics, which carried high margins at the time.

Dickerson remembers it as a hand-to-mouth existence, as few could afford the standard prices. A fax cost $3000, a mobile phone $5000. “It was a pretty exciting event when someone bought one computer. If I had a week – [of] which I can’t remember having too many – that I sold a computer and a mobile phone, that was all the cows come home.”

Soon he convinced the bank to give him his first business loan for $5000, which he blew the next day on a mobile phone. A year later he took on his first employee and then moved into the last vacant shop in the Centro shopping mall.

Not that he could afford to – instead, he knocked on the centre manager’s door and offered him $100 a month until another tenant showed up or he could afford proper rent.

Dickerson then took the biggest gamble of his working life. He stocked the shop with $10,000 worth of credit from his suppliers (mainly Tech Pacific) and hoped that he would sell enough by the end of the month to pay them back.

On the first day of the next month, Dickerson was still there, but only just. “It was really a struggle just to squeeze by, but once we’d done that one we knew we could keep going.”

By 1994 Dickerson could afford to pay rent as well as three salaries plus his own, and he signed a lease and did a major shop fitout. He also changed the company title from MAD Industries (an acronym of his name) to Axxis Technology.

With a bit of capital and acumen, Dickerson split off the cabling business of Axxis into another company called Comstall in 1996. In 1998 he did the same with the mobile phone business, opening another shop for that purpose alone in the same shopping centre.

Both companies did much better as separate entities. Mobile phone sales leapt from 30-40 a month to 150 phones a month. It’s still in operation 10 years later in the same location, and averages 200 phone sales a month.

The cabling business also did well, eventually winning more than 70 percent of its work outside of Axxis before Dickerson sold it off in 2004 for an undisclosed amount.

Axxis outgrew the shopping centre and moved to much larger premises in 2000. Despite Axxis making good profits that were increasing year on year, Dickerson realised that it would come to a very sudden halt in a matter of time – five years, according to his calculations.

A business model that relied on good margins was now outdated thanks to the commoditisation of the IT industry. The conclusions he drew, and the following steps he took to change his business model, he would eventually share at conferences all over the globe.

“When I’m talking to people around the world, they’ve all got the same story. All remember when we used to make good margins. You’d sell the hardware and make good money on it, and when [the client] rang up two weeks later [with] a problem, it seemed like good customer service to fix it.

“When they rang up three months later [with a problem], was it the fault of our installation or was it something that just happens in IT, or was it the fault of the client? Do you charge? How much do you charge? Is there a call-out fee?”

Dickerson looked for alternative models that gave a fair reward for the skills and talent of Axxis’ staff. He assigned one staff member the role of developing this new service-based business, but after a couple of weeks he had drawn a blank. “Two months later he said to me, ‘It’s a bit hard.’ And I said to him, “Maybe you’re too busy, here I’ll give it to Billy.”

The task passed through three staff over six months, but no-one could come up with answers. “In the end I said, ‘If you guys haven’t got the time to do it, I’ll do it.’ It took me several years to get to the point that we could roll something out.”

But moving from hardware to services was not tenable under a conventional break-fix model, which relies on things going badly to win work. If Axxis did a great job on an installation, and put sound practices and quality hardware in place, clients would have less reason to call them to fix things.

“Every morning I’d walk in with a bunch of pillows under my arm, hand them to staff and say, ‘right everyone, kneel down and pray to God that we have something break down this week so that we can make some money,’” jokes Dickerson. Under break-fix, “the better a job that you do, the quicker you go broke. When you sit back now it just seems so illogical.”

The two big changes were to estimate repair work rather than bill by the hour, and to charge clients a regular monthly fee to keep the network running. The later change required a little re-education of customers’ expectations: instead of wondering what you’re paying for at the end of a trouble-free month, you should be happy with your productivity and quality of our maintenance practices, Dickerson told them.

Operating under the new fixed price model, Axxis won several awards including 2004 Microsoft Platform Partner of the Year in the small business category. The service level agreement model was introduced in 2005, the year Dickerson was named the world’s number one SMB consultant by SMB Nation.

A year later, Dickerson was grinning on a stage wearing an “I love Dubbo!” t-shirt, waving a trophy for Microsoft worldwide partner of the year in the sales and marketing small business specialist category. Axxis now has a turnover of $4 million and 20 staff. The phone business has five staff.

Later, Dickerson was approached by two men at a conference in Amsterdam he was speaking at. The two wanted to buy his SLA model as a blueprint for their own restructuring. Dickerson wasn’t even sure this was possible, but after working with his lawyer and accountant in Dubbo he came up with a packaged product called SLAM, for service level agreement model.

SLAM contains the methodology, spreadsheets and documents which Axxis itself uses, and has sold 300 copies on a sliding scale that starts at US$999 or AU$1500, depending on number of users.

“We’ve got clients in nine countries who are using exactly what we use in our business,” said Dickerson.

Reflecting on his achievements, Dickerson said resellers shouldn’t consider their location as a limitation on what is possible. “The only thing that limits you is your mindset or attitude. Some people I know in businesses in country towns have said, ‘Wow, you managed to do that and you are in a country town’. But I don’t see there is any reason to do whatever you want to do from anywhere.”

Operating as a country reseller is considerably tougher, and those who survive only do so through establishing good practices. “People think it’s easier to do it in regional areas, but we’re finding it tougher.”

Unexpectedly, country towns can be far more competitive than capital cities. At one stage there were 40 computer retailers in Dubbo servicing a population of 40,000.

A small base means high quality customer service is imperative. “Word of mouth is great if you are good in a country town, and if you do anything wrong it’s terrible.”

Apart from the trophies in the pool room, the fact that Axxis counts clients from Sydney shows how a good reseller is worth hanging onto. One of those Sydney clients told Dickerson the Axxis technicians feel like part of their staff. “But we’re 400 kilometres away, how can they feel like that? The only way is by having exceptional service. Location is almost irrelevant.”

Dubbo – a gateway to IT

By

Sholto Macpherson

on Apr 2, 2008 4:48PM

Got a news tip for our journalists? Share it with us anonymously here.

Partner Content

.png&h=142&w=230&c=1&s=1)

How mandatory climate reporting is raising the bar for corporate leadership

_(21).jpg&h=142&w=230&c=1&s=1)

Empowering Sustainability: Schneider Electric's Dedication to Powering Customer Success

_(27).jpg&h=142&w=230&c=1&s=1)

Promoted Content

Why Renew IT Is Different: Where Science, AI and Sustainability Redefine IT Asset Disposition

Shared Intelligence is the Real Competitive Edge Partners Enjoy with Crayon

Think Technology Australia deliver massive ROI to a Toyota dealership through SharePoint-powered, automated document management

.jpg&w=100&c=1&s=0)

_(1).jpg&q=95&h=298&w=480&c=1&s=1)