Security and privacy advocates fear that 'smart' style personal objects (such as passports and credit cards) embedded with RFID tags have the potential to do more harm than good, particularly if recent news reports of 'RFID hacking' are anything to go by.

More so, Patrick Redmond, a long serving ex-IBM employee, lecturer and author on RFID technology, has come up with an eyebrow-raising new conspiracy about RFID tags: he believes that the television changeover from analogue to digital is not just for our entertainment, but is being used as a way to create the necessary bandwidth, which will be required to facilitate the introduction of RFID tagged objects into everyday items.

Though the conspiracy nuts might need not worry: RFID's are already here and companies are turning to new ways to keep tabs on us.

These RFID-stamped items range from the obvious (passports) to the not-so-obvious. In the latter camp, these include personal body products such as shaving blades.

Gillette, one of the largest shaving brands in the world, have been openly criticised by some online bloggers for embedding RFID chips in the packaging of some of their razor products.

A Boycott Gillette website has been set up to protest privacy fears.The website attacks Gillette for setting up spy cameras that snap pictures of purchasers whenever the tag detects being taken off the shelf.

The technology was developed at MIT labs, where it is better known as smart shelf technology, which may or might not be targeted towards thieves or as a method to better understand the shoppers who purchase these products.

Most of the time though, says Redmond, we won't even know we're wearing a tag. Redmond claims that RFIDs can track our every movement, a conceit not lost on the US military. The same kind of technology is now used in the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan to track wayward soldiers, although privacy concerns loom over just how the RFID tags work to keep marines safe.

But not everybody shares the view that RFIDs are bad. Some RFID advocates just don't see the same risks, inlcuding blogger Mark Roberti, who has written an interesting piece rebutting some of the recent hacking reports for RFID journal, the web's portal for everything RFID.

Introducing 'Little Brother'

Even though the first true RFID was invented in 1973, it's taken us 36 years to acutely realise the consequences of embedding the electronic tags into everyday life. It's not just a useful tool for freight and delivery automation services say security experts (where it was primarily used for years), but as a tool that more and more governments are frequently turning to, in order to keep tabs on our whereabouts.

Just ask certain American Express card holders in the US. Last year, Engadget ran a piece about how easy it was to hack an RFID-based credit card using an $8 reader. Other travel smartcards such as the UK oystercard have suffered similar fates; they too contain similar RFID tags, capable of transmitting data into the wrong hands.

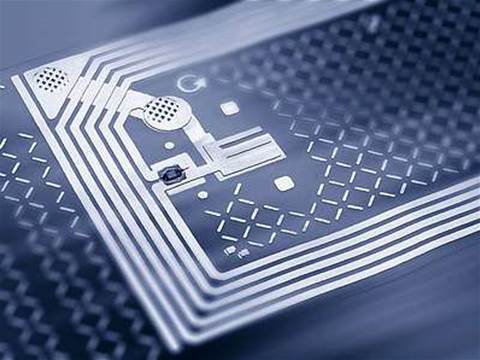

Three types of RFID chips currently exist and most ship with internal battery sources. Newer types of RFID chips contain super batteries that can last for up to one hundred years; long enough to fulfil the job of transmitting and storing data over a person's lifespan.

Each RFID carries its own unique serial code and each transmits a wireless radio frequency over a number of metres. However, this personal wireles signal can often tell more about the user than we think.

RFIDs are everywhere

The RFID privacy issue becomes harder to ignore when you consider that almost 1.8 billion RFID tags were sold in 2005 alone.

That number is also likely to be a whole lot larger now that RFIDs are embedded in credit cards, driver licences and other everyday documents across the world.

In addition, drug companies are also turning to RFIDs to ward off counterfeit drug production. Big names such as Viagra have turned to RFID tags. And the same thing goes for software and movies, as piracy becomes a bigger issue, especially for DVDs.

Even our food supply, starting at the feedlot, has the potential to be 'tracked', based on the creation of RFID ink, which can be used to tattoo livestock - a patent was filed in 2008. This had lead to fears that the same technology could be used to track people in the future, says Computer Weekly.

Even today, there are hopes that RFID will track patients and their doctors in the health system of European nations, as explained in a new report ,carried out by the European commission.

Wireless network: RFIDs need bandwidth

For that many RFID tags to transmit over the analogue waveband, there's going to be some serious bandwidth necessary to allocate all those frequencies. Redmond believes that by 2017, there will be over 1 trillion RFID tags in existence, a market worth more than $US25 billion annually.

In a statement made to Vitalisnews, Redmond spoke about the technical need to increase the space (bandwidth) needed for these RFIDs:

"The increased use of RFID chips is going to require the increased use of the UBF [UHF] spectrum. ...They are going to stop using the [UHF] and VHF frequencies in 2009. Everything is going to go digital (in the U.S.). Canada is going to do the same thing", said Redmond.

(-continued next page-)

RFID tracking

The growing number of RFIDs has led to fears that the same technology could be used to track people. The RFID Gazette warns that employers have the upper hand to keep tabs on their employees by insisting on making employees wear the chips, whether it be directly or indirectly (think of a courier or a routine service person).

Everyday smart cards which provide access to employees into most corporate buildings, contain RFIDs that can tell a boss much more about the employee than a simple swipe to open the door. The data is easily catalogued by a computer and can reveal the times the employee arrives at work, finshes and much more.

But when it comes to RFID hacking, Ebay is proving a winner for enterprising data skimmers, who seek the RFID data. According to a Los Angeles Times report, San Francisco native Chris Paget armed himself with a cheap Motorola reader purchased on the auction site and scanned the hilly streets of his city in search of accessible and unsecured RFIDs. Which is most of them, really.

Within an hour Paget had found what he was looking for: the unique serial codes contained in RFID-equipped passports. The test proved how easy it was for people to download the codes and potentially identify people without their knowledge, and silently track the person if they needed too.

The RFID breach already has a name in security circles: Little Brother. And this ability to send and receive data to a reader (or scanner) is happening right across our industrialised world, at airports, through border crossings and even on an ordinary trip to the supermarket.

The future for RFID

For now, the jury is out until more studies are done on the security implications of RFIDs.

Meanwhile, the technology is getting more sophisticated. RFID chips are now so small in fact, that they measure no longer than a grain of rice, if not much smaller.

Some state laws in Australia even make it mandatory to chip newly purchased cats and dogs in Australia, a bond between man and pet, that keeps us well within the reach of RFIDs whether we like it or not. More troublingly however is the claim that RFID use in our pets may cause cancer.

For more reading, The RFID journal and RFID Gazette have a great collection of articles and topics on the subject, while Patrick Redmond's lectures on the dangers of RFID can be found on his website.

_(27).jpg&h=142&w=230&c=1&s=1)

.png&h=142&w=230&c=1&s=1)

_(21).jpg&h=142&w=230&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&w=100&c=1&s=0)